Heavy Metal

There’s no sound quite like the rhythmic striking of metal by another metal object. It’s a sound that instantly draws my ears and focus. Maybe I was a blacksmith in a former life, who knows. However what I was hearing wasn’t blacksmithing. There is a high pitched ping that is distinctive to iron and steel. What I was hearing was coppersmithing. Instead of a ringing, I hear a thwack-thwack-thwack. The softer metal stole the reverberation from the thick raising stake the man was forming the copper sheet around.

There’s no sound quite like the rhythmic striking of metal by another metal object. It’s a sound that instantly draws my ears and focus. Maybe I was a blacksmith in a former life, who knows. However what I was hearing wasn’t blacksmithing. There is a high pitched ping that is distinctive to iron and steel. What I was hearing was coppersmithing. Instead of a ringing, I hear a thwack-thwack-thwack. The softer metal stole the reverberation from the thick raising stake the man was forming the copper sheet around.  Just as Karina, her son Gerardo, and I stepped from sales shop into the workshop, the smith turned on the blowers for the forge. In just a few moments the whole space, despite being partially outdoors, filled up with smoke. The smith wore a green polo, black pants, and running shoes, not exactly what I think of as approved workwear for a fiery, metal bashing environment. Then I remembered the lack of controls on getting a driver’s license in Mexico and realized their version of OSHA might be a touch relaxed too. He shuffled over to a woodpile stacked high with slats of raw wood. He grabbed a few chunks and gently tossed them onto the rising flames before he took note of us. He greeted us with a warm “¡Buenas tardes!”

Just as Karina, her son Gerardo, and I stepped from sales shop into the workshop, the smith turned on the blowers for the forge. In just a few moments the whole space, despite being partially outdoors, filled up with smoke. The smith wore a green polo, black pants, and running shoes, not exactly what I think of as approved workwear for a fiery, metal bashing environment. Then I remembered the lack of controls on getting a driver’s license in Mexico and realized their version of OSHA might be a touch relaxed too. He shuffled over to a woodpile stacked high with slats of raw wood. He grabbed a few chunks and gently tossed them onto the rising flames before he took note of us. He greeted us with a warm “¡Buenas tardes!”  Behind him was a forge unlike any I had seen before. First off, it looked like an amorphous mass of mud or concrete on the ground with embers, ash, and unburnt wood piled up in front of it. On top of the mass was a copper tub who’s function I never figured out. From what I could figure, it had to have been some kind of protection for the blower tubes that ran underneath the pile of embers and wood. A mass that big with a tub of water on top would certainly mitigate the amount of heat going back to the blower motor or in the old days the poor bastard working the bellows. This outbuilding had a steeply sloped roof that funneled most of the smoke skyward, but certainly not all.

Behind him was a forge unlike any I had seen before. First off, it looked like an amorphous mass of mud or concrete on the ground with embers, ash, and unburnt wood piled up in front of it. On top of the mass was a copper tub who’s function I never figured out. From what I could figure, it had to have been some kind of protection for the blower tubes that ran underneath the pile of embers and wood. A mass that big with a tub of water on top would certainly mitigate the amount of heat going back to the blower motor or in the old days the poor bastard working the bellows. This outbuilding had a steeply sloped roof that funneled most of the smoke skyward, but certainly not all. At the National Museum of Copper, three artisans gathered in the courtyard under a wooden roof. The two men hammered away, while the woman, Carmen, carefully scraped away designs in a copper plate. The older of the two men hammered out rivets that would be used to put handles on the cooking pans stacked next to his feet, while the younger hammered leaf and vine designs into copper strips. The younger man’s movements were as sure as a chef chopping onions. First he would draw the pattern he wanted in sharpie and then with a hammer and a thin piece of rebar, he had fashioned to the shape he wanted, would create the pattern. When asked, the older man told us that he had been working in copper for seventy years, he was eighty-two. The younger man was a spritely sixty-three and might as well have still been an apprentice with only fifty-two years under his belt. I decided out of politeness, not to ask Carmen how long she had been working copper for, but it had to have been at least as long as the younger man considering her equally deft touch.

At the National Museum of Copper, three artisans gathered in the courtyard under a wooden roof. The two men hammered away, while the woman, Carmen, carefully scraped away designs in a copper plate. The older of the two men hammered out rivets that would be used to put handles on the cooking pans stacked next to his feet, while the younger hammered leaf and vine designs into copper strips. The younger man’s movements were as sure as a chef chopping onions. First he would draw the pattern he wanted in sharpie and then with a hammer and a thin piece of rebar, he had fashioned to the shape he wanted, would create the pattern. When asked, the older man told us that he had been working in copper for seventy years, he was eighty-two. The younger man was a spritely sixty-three and might as well have still been an apprentice with only fifty-two years under his belt. I decided out of politeness, not to ask Carmen how long she had been working copper for, but it had to have been at least as long as the younger man considering her equally deft touch.  She gripped a copper plate covered with a black tar-like substance and with a scrap piece of copper scraped away a design that she had scratched into the black. The plate she was working would eventually end up in a chemical bath of uric acid to slowly eat away at the exposed copper. The tar coating was there to protect the design from the acid and would be removed later to expose the shiny copper underneath.

She gripped a copper plate covered with a black tar-like substance and with a scrap piece of copper scraped away a design that she had scratched into the black. The plate she was working would eventually end up in a chemical bath of uric acid to slowly eat away at the exposed copper. The tar coating was there to protect the design from the acid and would be removed later to expose the shiny copper underneath. The only thing that was missing from my trip to Santa Clara del Cobre was an actual copper smithing class. Unfortunately they don’t do those on Mondays, but there are workshops that do offer it, so I’ll just have to go back. The best I could do to soothe my rejection was to listen to heavy metal music on our hour long ride back to the house.

The only thing that was missing from my trip to Santa Clara del Cobre was an actual copper smithing class. Unfortunately they don’t do those on Mondays, but there are workshops that do offer it, so I’ll just have to go back. The best I could do to soothe my rejection was to listen to heavy metal music on our hour long ride back to the house.

See how the artisans work copper into beautiful designs.

____________________________________________________________

Cultural Definitions Of Time

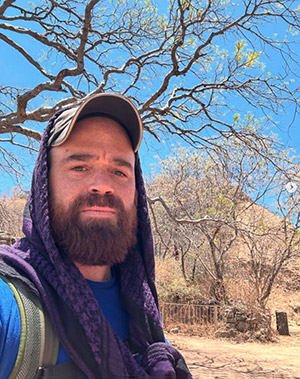

by Thaddeus Tripp Ressler

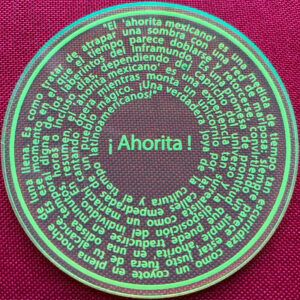

“The Mexican ‘ahorita’ is a measure of time as elusive as a coyote in the middle of a full moon. It’s like trying to catch a shadow with a butterfly net. It always seems just out of reach. It’s that moment when time seems to bend and twist, turning a simple ‘ahorita’ into a temporal odyssey worthy of the labyrinths of the underworld. It’s a promise of promptness that can translate into minutes, hours, or even days, depending on the whims of the universe and the individual’s disposition. In short, the ‘Ahorita Mexicano’ is an experience as surreal as a singing mariachi band performing while riding a unicorn through the cobblestone streets of a magical town. A true gem of Latin American culture and time!” ~Ahorita! by Ozwaldo Olvera Trejo

Ahorita is a word that means many things to many people in Mexico. Translated directly it means ‘right now’, but it’s true meaning comes down to the person saying it, the timing of it, and the context. It could mean right now, if that person is in front of you and you’ve just asked when they were planning on leaving the party. Then again, it could mean right after he says goodbye to everyone in his immediate and extended family and has taken multiple shots of tequila with them. It is widely accepted here, and joked about often. Mary Carmen’s son, Oswaldo, lovingly makes key chains similar to the plaque above as tribute. In a country where showing up on time to a party is considered uncouth and downright rude, Mexican culture demands a word like ahorita. It is both lie and fact, honest desire and mythic brush-off. It can be used to postpone or indirectly cancel plans without ever having to say the actual words. On the phone it could mean that person is still in bed and considering what clothes to wear, despite having told that they’re coming over, ahorita. It requires a knowledge and understanding of the person you’re speaking with. If a more serious person says it to you, feel free to take it more seriously. If a more… carefree person, says it, be more liberal with the grains of salt you’re consuming. If even a drop of alcohol is involved, “may the odds be ever in your favor.” Everywhere I’ve been has something akin to this. We all have friends that are chronically late or blow us off by saying one thing and meaning another. A sizable number of people I know get annoyed and call it irresponsible. However, my Dominican and Jamaica friends in New York shrug, raise an eyebrow, and state “Island Time”, like I should’ve known better. My black friends in Chicago laughingly call it “CPT”, or Colored People Time. However, nothing I’ve come across seems to have quite the elegance, finesse, and cultural understanding of the singular word that is the Mexican, Ahorita.

Ancient Zapotec Rugs & Old School Mezcal

by Thaddeus Ressler

Jorge asked for volunteers. I laughed considering it was just me and Gabby. He walked over to a cactus paddle that was hanging from a rafter. It had a white dust all over it that made me think that it was just a dusty ornament. He plucked something out of it and walked back over to us.  He motioned for me to hold out my hand, and I did. He dropped a small white thing in the center of my palm. It looked about the size of a fat grain of rice, which might have been why he called it un grano. Upon closer inspection I had no idea what this foreign little thing reminded me of, maybe a tiny pinecone. Jorge grabbed my hand and took his pointer finger and crushed the thing into my hand. As he started to rub circles into my palm a bright red circle appeared as if by magic. Cochineal!

He motioned for me to hold out my hand, and I did. He dropped a small white thing in the center of my palm. It looked about the size of a fat grain of rice, which might have been why he called it un grano. Upon closer inspection I had no idea what this foreign little thing reminded me of, maybe a tiny pinecone. Jorge grabbed my hand and took his pointer finger and crushed the thing into my hand. As he started to rub circles into my palm a bright red circle appeared as if by magic. Cochineal!

I knew it somewhere in my brain! It’s a bug that lives on cacti. Specifically the Nopal cactus, which is a farmed crop here in Mexico. The young paddles, known as nopales, are harvested and cooked up and used in everything from salads and soups, to grilled meats dishes and tacos. The bright red fruits, which Mexicans call tuna, are sweet and juicy, reminiscent of dragon fruit, or watermelon. The cochineal bug infects the pads of the cactus spreading a white substance over them. They’ll cluster and then spread, clustering again, and then spreading again. Those little guys produce carmine, a natural dye, that indigenous people of the Americas have been using on textiles for over two thousand years. One only needs to brush the bugs off the plant and crush it up, and voila, a rich red dye.

But then our new friend showed us something even cooler. He started doing chemistry on my hand. He squeezed a bit of lime juice into my hand the color turned from deep red into a brighter red. Then he added a bit of ground up marigold, turning it to an orangey-red. A bit of baking soda rubbed into the pinky side of my palm, made it transform to a plum color. I can’t remember how he made the green color, but by the end my hand looked like a painters palette.

But then our new friend showed us something even cooler. He started doing chemistry on my hand. He squeezed a bit of lime juice into my hand the color turned from deep red into a brighter red. Then he added a bit of ground up marigold, turning it to an orangey-red. A bit of baking soda rubbed into the pinky side of my palm, made it transform to a plum color. I can’t remember how he made the green color, but by the end my hand looked like a painters palette.

After washing my hands, it was on to the weaving. Thanks to my parents, I am quite familiar with looms. I spent a whole summer weaving with a loom that my grandfather and I had modified to make ribbon fabric. I hadn’t made any designs, just placed the ribbons as aesthetically as my seventeen year old brain could muster. These guys, however, were putting animals and geometric designs into their wool rugs. He showed us how they would weave individual bundles of yarn that make up the weft(across), to match the outline drawn onto the warp yarns(lengthwise). Then if it was at the front of the weft he could pull back on the beater, or if the beater couldn’t reach it, he would use a comb to pull the yarn tight into the rug. Jorge told us the stories behind the patterns on the rugs. The steps represented the steps of life, and the geometric spirals represented death and rebirth. The central part was meant to be the eye of god.

This had turned into a really fun and educational day. Gabby and I had been packing in the sights as best we could, since I only had a week in Oaxaca. Before this we had come from down the road at a mezcaleria, where we learned how mezcal is made. Well, because of my tenure behind the bar, I’ve actually taken many classes on the fermentation, distillation, barreling, and bottling processes. However, it was very cool to see the mezcal process up close and personal in a place that’s actually making it, rather than seeing the pictures or videos on a screen. Nothing can compare to the burnt wood smells of the roasting pit, or the fruity funk of the agave mash fermenting. Plus, not a one of those classes I took offered up slices of freshly roasted agave to try, and that transformed the way that I thought about the flavors in Mezcal and Tequila. It had a sweet-sour, earthy, honey thing going on in it. Because it’s so complex, it’s hard to pinpoint exact flavors, but good lord did it taste good.

This had turned into a really fun and educational day. Gabby and I had been packing in the sights as best we could, since I only had a week in Oaxaca. Before this we had come from down the road at a mezcaleria, where we learned how mezcal is made. Well, because of my tenure behind the bar, I’ve actually taken many classes on the fermentation, distillation, barreling, and bottling processes. However, it was very cool to see the mezcal process up close and personal in a place that’s actually making it, rather than seeing the pictures or videos on a screen. Nothing can compare to the burnt wood smells of the roasting pit, or the fruity funk of the agave mash fermenting. Plus, not a one of those classes I took offered up slices of freshly roasted agave to try, and that transformed the way that I thought about the flavors in Mezcal and Tequila. It had a sweet-sour, earthy, honey thing going on in it. Because it’s so complex, it’s hard to pinpoint exact flavors, but good lord did it taste good.

A quick walkthrough of the Mezcal process is as follows: allow agave to grow for ten years, cut all the leaves off and pull “piña” out of the ground, cover with aforementioned leaves and roast piñas for a few days in a pit loaded with coals underneath and over top. After that mash the piñas under a huge circular millstone dragged in circles by an unamused looking horse or donkey. Then take the mashed up agave and mix with water to extract all the sugars out and then allow to ferment. Strain out pulp from mash and allow to continue fermenting for another week or two. Then distill out the alcohol, maybe even a few times. Then serve with chili-salt and a wedge of lime.

A quick walkthrough of the Mezcal process is as follows: allow agave to grow for ten years, cut all the leaves off and pull “piña” out of the ground, cover with aforementioned leaves and roast piñas for a few days in a pit loaded with coals underneath and over top. After that mash the piñas under a huge circular millstone dragged in circles by an unamused looking horse or donkey. Then take the mashed up agave and mix with water to extract all the sugars out and then allow to ferment. Strain out pulp from mash and allow to continue fermenting for another week or two. Then distill out the alcohol, maybe even a few times. Then serve with chili-salt and a wedge of lime.

It doesn’t seem like it, but this is a similar process to making any other kind of alcohol. Want to make the most basic beer? Just boil malted grain to extract all the sugars, strain it out, and then ferment it with yeast for a few weeks. For wine you would mix fruit juice with yeast and then let it ferment for a few weeks. Then to make liquor from it, you would distill the alcohol out of it. It just requires the right equipment, which can be improvised handily for under $100. That said, there’s good reasons why home distilling doesn’t get the same allowances that home brewing does. Click this link to see a short video Agave Mash.

At the end of the tour we got to taste several varieties that they happened to have for sale. Some were specific agave varietals, others were infused with fruits or herbs. I bought a bottle of an agave varietal called Tobala for a friend back home, and Gabby grabbed one for herself because in her words. “This is Mexico. You don’t know when somebody comes to the house. You might need Mezcal.”

Testing And The Art Of Driving On Mexican Roadways

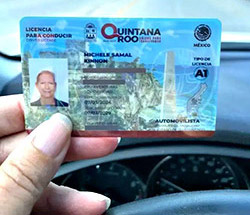

Growing up in New Jersey, a place where there is a rule, regulation, law, directive, and tax on everything that a person does, it seems crazy that you wouldn’t need certification to drive on public roads. Yet, those certifications have never stopped Americans from being terrible drivers. It does, however, give us the comfortable illusion of safety and competence. And this is coming to you from someone who has traversed the entire East Coast, all over the Midwest, and Southwest. I’ve also driven most of the highways, byways, state, county, and surface roads of the three largest metropolises of the United States, as well as a handful of smaller ones too. I have driven in thirty-eight of our fifty states, and I can say with absolute certainty that the United States has no shortage of horrendous drivers in it. Each and everyone of them went through “thorough” training and testing.

Growing up in New Jersey, a place where there is a rule, regulation, law, directive, and tax on everything that a person does, it seems crazy that you wouldn’t need certification to drive on public roads. Yet, those certifications have never stopped Americans from being terrible drivers. It does, however, give us the comfortable illusion of safety and competence. And this is coming to you from someone who has traversed the entire East Coast, all over the Midwest, and Southwest. I’ve also driven most of the highways, byways, state, county, and surface roads of the three largest metropolises of the United States, as well as a handful of smaller ones too. I have driven in thirty-eight of our fifty states, and I can say with absolute certainty that the United States has no shortage of horrendous drivers in it. Each and everyone of them went through “thorough” training and testing.  On that trip I had opted for a front row seat, thinking this was going to be like the luxurious coach I had taken in the opposite direction. It was not. More than that, the driver was not the same relaxed gentleman we had on the way to Puebla. This man drove like he had just stolen the bus and was trying to flee the country in the most convoluted way possible. Every turn felt like a test of my core strength. I averted my eyes when he overtook vehicles, I braced for impact every time he came right up to the bumper of slow-moving vehicles that hadn’t moved to the shoulder fast enough. If I had pearls, they would have been clutched every time he took a turn that, by my estimation, came far too close to other vehicles or buildings, which was literally every single one of them. Yet, the man never flinched, never stopped, there were times that he didn’t even stop to let people jump on. Cucumbers dream of being this cool. He was as sure in his movements as a surgeon doing the routine removal of a mole. The only thing that ever seemed to slow him down were the topes (pronounced TOE-pace), the Mexican word for speed bumps.

On that trip I had opted for a front row seat, thinking this was going to be like the luxurious coach I had taken in the opposite direction. It was not. More than that, the driver was not the same relaxed gentleman we had on the way to Puebla. This man drove like he had just stolen the bus and was trying to flee the country in the most convoluted way possible. Every turn felt like a test of my core strength. I averted my eyes when he overtook vehicles, I braced for impact every time he came right up to the bumper of slow-moving vehicles that hadn’t moved to the shoulder fast enough. If I had pearls, they would have been clutched every time he took a turn that, by my estimation, came far too close to other vehicles or buildings, which was literally every single one of them. Yet, the man never flinched, never stopped, there were times that he didn’t even stop to let people jump on. Cucumbers dream of being this cool. He was as sure in his movements as a surgeon doing the routine removal of a mole. The only thing that ever seemed to slow him down were the topes (pronounced TOE-pace), the Mexican word for speed bumps.  These “sleeping policemen”, are ubiquitous in Mexico. The only place they don’t exist is on the high speed toll roads. The smaller the road the sooner you can expect them. For instance on the one-way streets of Zacatlán, they come at least once per block. You can count on them popping up least every kilometer on a bigger road. They’ll stretch them out further in farm country, where you mostly get them at crossings or more populated areas. I even saw a couple of them on dirt roads, which makes no sense to me. They vary in age, height, shape, and markings. Some are a serpentine row of steel half-spheres crossing the road, some are eight inch wide asphalt rows with a slope so sharp it feels vindictive. Others are tall and long enough to make a bus rock like a boat in stormy seas. To top it all off, the Mexican government doesn’t seem to value the universality or consistency of road signage. Nor do they seem to care if these topes have markings on them that signify their presence at all! On more than one occasion these unmarked topes afforded me an unexpected Spanish lesson in the proper use of foul language.

These “sleeping policemen”, are ubiquitous in Mexico. The only place they don’t exist is on the high speed toll roads. The smaller the road the sooner you can expect them. For instance on the one-way streets of Zacatlán, they come at least once per block. You can count on them popping up least every kilometer on a bigger road. They’ll stretch them out further in farm country, where you mostly get them at crossings or more populated areas. I even saw a couple of them on dirt roads, which makes no sense to me. They vary in age, height, shape, and markings. Some are a serpentine row of steel half-spheres crossing the road, some are eight inch wide asphalt rows with a slope so sharp it feels vindictive. Others are tall and long enough to make a bus rock like a boat in stormy seas. To top it all off, the Mexican government doesn’t seem to value the universality or consistency of road signage. Nor do they seem to care if these topes have markings on them that signify their presence at all! On more than one occasion these unmarked topes afforded me an unexpected Spanish lesson in the proper use of foul language. I got to experience highway topes on day one with Dick Davis, when we took a taxi from Mexico City to Zacatlán. There must have been at least a hundred of them in the three hour drive. Apparently there aren’t as many of them in Mexico City, because it seemed like our cabby’s first experience with them too. Many of them were hit at speeds well in excess of what his little car’s suspension could handle. Each one earned a quiet curse and/or grunt from all three of us. In one case, Dick and I hit the roof of the cab with enough force to stun us and make us slide deep down into our seats for fear that it might happen again.

I got to experience highway topes on day one with Dick Davis, when we took a taxi from Mexico City to Zacatlán. There must have been at least a hundred of them in the three hour drive. Apparently there aren’t as many of them in Mexico City, because it seemed like our cabby’s first experience with them too. Many of them were hit at speeds well in excess of what his little car’s suspension could handle. Each one earned a quiet curse and/or grunt from all three of us. In one case, Dick and I hit the roof of the cab with enough force to stun us and make us slide deep down into our seats for fear that it might happen again.  Lying in bed in Oaxaca, weeks later, I was trying to figure out how I could make sense of all of this, especially those damn topes. I thought about the fact that Mexico is a country that enjoys its drinking, a lot, and their drivers don’t go through testing. My mind reeled at the idea that swearing to a government official that you know how to drive, plus a birth certificate and proof of address, was all that was necessary to get a driver’s license. From that angle though, all those topes started to make a little more sense to me. It’s hard to cause a massive car wreck when you can’t get over 35mph. Could you, sure, but it had to limit the possibility tremendously. Hell, I’d be willing to bet that most of the drunk driving accidents are caused by very short people, because as Dick and I can attest, smacking your head into the roof of a car is a sobering experience.

Lying in bed in Oaxaca, weeks later, I was trying to figure out how I could make sense of all of this, especially those damn topes. I thought about the fact that Mexico is a country that enjoys its drinking, a lot, and their drivers don’t go through testing. My mind reeled at the idea that swearing to a government official that you know how to drive, plus a birth certificate and proof of address, was all that was necessary to get a driver’s license. From that angle though, all those topes started to make a little more sense to me. It’s hard to cause a massive car wreck when you can’t get over 35mph. Could you, sure, but it had to limit the possibility tremendously. Hell, I’d be willing to bet that most of the drunk driving accidents are caused by very short people, because as Dick and I can attest, smacking your head into the roof of a car is a sobering experience.Flores de la Primavera

by Thaddeus Tripp Ressler

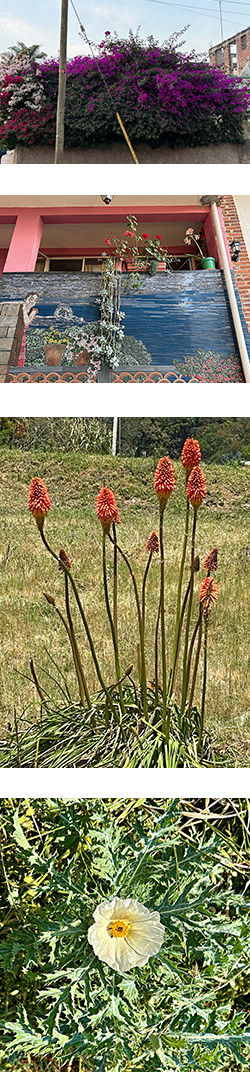

Spring in Mexico, even in the mountains is a very warm affair. It’s only the beginning of April and already hitting the mid-eighties. A far sight from the sub-zero temperatures I was dealing with just two months ago in Colorado, though it’s certainly just as dry. None of that seems to bother the flowers though. There’s an explosion of color on the streets of Zacatlán.

Spring in Mexico, even in the mountains is a very warm affair. It’s only the beginning of April and already hitting the mid-eighties. A far sight from the sub-zero temperatures I was dealing with just two months ago in Colorado, though it’s certainly just as dry. None of that seems to bother the flowers though. There’s an explosion of color on the streets of Zacatlán.

Turning a corner can put you face to face with a Paperflower bush hanging over walls or through a gate spilling into and over the sidewalk making beautiful canopies of orange, pinks, reds, and purples.

I found feral Fuchsias growing out of a corner of a small church.

Geraniums in pink and red give little pops of color to balconies and windowsills.

I even saw a beautiful Chilean Jasmine bloom in pink winding it’s way up a staircase.

High up in Popotuhuilco, I found Red Hot Pokers blooming, and waiting for hummingbirds.

Blue Lily’s bunched at the top of a tall stalk in a garden where a White Foxglove was showing off a stack of blooms and buds, two feet high.

But the most interesting to me is the Spiky Mexican Pricklypoppy. This thorny relative to the thistle has beautiful white or yellow flowers, and seems to only grow in forgotten places.